Transcript

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Rob Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is The 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and whether The Road should be a reality TV show. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

If civilisation collapsed, what essential information would speed up our recovery the most?

It’s a fun dinner party topic and a regular feature in science fiction novels.

But Lewis Dartnell actually tried to write a book with all that most crucial science and technology, which he published as The Knowledge.

It’s both an entertaining read and an informative one that has heavily informed 80,000 Hours’ views on whether and how quickly humanity might recover from a major global catastrophe.

My research colleague Luisa Rodriguez and I wanted to hit him with some practical questions he didn’t get to in the book, including whether it’s time to set up a serious institute to collect and safeguard useful knowledge for future generations. Fortunately, Lewis was down to call in from home, despite having become a dad just a few months ago.

No housekeeping this week, so without further ado, I bring you Lewis Dartnell.

The interview begins [00:00:59]

Rob Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with Lewis Dartnell. Lewis is a science communicator and author of multiple books that I know are popular among listeners to this show, including The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Civilization in the Aftermath of a Cataclysm and Origins: How the Earth’s History Shaped Human History. The Knowledge actually won multiple awards, including The Times Science Book of the Year, and it was also a New York Times and Sunday Times bestseller.

Rob Wiblin: Lewis got his start in biology at Oxford, and then astrobiology at University College London. He’s now a professor in science communications at the University of Westminster. Thanks for coming on the podcast, Lewis.

Lewis Dartnell: Hi. Thank you so much for having me. I’ve been looking forward to this. I think this is going to be quite an interesting chat.

Rob Wiblin: Us as well. And I say “us” because I’m joined today by my colleague and previous guest of the show, Luisa Rodriguez, who has thought a lot about how humanity might recover from various different sorts of collapses. Welcome back, Luisa.

Luisa Rodriguez: Thanks, Rob. I’m happy to be back.

Rob Wiblin: I hope we’re going to get to talk about whether humanity should seriously invest in a more comprehensive version of The Knowledge, and also what’s most likely to impede our recovery should things really go belly up. But first, as we always ask, what are you working on at the moment and why do you think it’s important?

Lewis Dartnell: So as you mentioned, my actual academic field of research is in astrobiology. I’ve got two PhD students at the moment, and one of them is looking with me into aspects of what signs of life on Mars we’d be looking for with our next-generation Mars rovers. So, so-called biosignatures, and how those are effectively nuked by the cosmic radiation on Mars — how long would these things stick around for before we could detect them?

Lewis Dartnell: Then the other half of my career in the professorship at University of Westminster is in science communication. I’ve been working on the new book. It will be book five. The Knowledge, the one we’re talking about today, is book three. Trying to balance the science writing and communication against the science research is something I really enjoy.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I think you might be slightly burying the lede as well, because you’ve got something else going on in your life at the moment, right? That might be trumping the work the last few months.

Lewis Dartnell: I now have a seven-week-old baby, Sebastian. Who was a bit boring at first, because he mostly slept and then just ate, which wasn’t really something I’m involved in now. But we had our first smile this week, and it just broke my heart. And it is the most wonderful thing in the world. I’m all about being a father now.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Sleeping and eating are things close to my heart.

Lewis Dartnell: Well, me too. It’s just not particularly interactive when you’re not getting involved in it.

The biggest impediments to bouncing back [00:03:18]

Rob Wiblin: OK, so let’s jump to the punch here. We’ve got this big common interest in understanding how humanity would recover from a major catastrophe that knocked us back a long way. Collecting a bunch of information that would be useful for survivors of a disaster was the topic of your book, The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Civilization in the Aftermath of a Cataclysm. To get straight to the most important issues here, what’s one thing you think humanity will find especially difficult — oh, sorry — would find especially difficult about recovering?

Lewis Dartnell: Do you know something that I don’t know?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, sorry. No, knock wood. Would find especially difficult about recovering to our level of technology, say after a pandemic that killed 90% of the population, or something around that level?

Lewis Dartnell: So that’s the premise of The Knowledge. I feel I should presage my answer by saying, I wrote the book not as a prepper, not as a survivalist, not as someone who thinks the world is about to end — although I’m sure we’ll get into a discussion about what existential hazards and risks are out there. But I wanted to use this notion of the loss of everything that we take for granted in our everyday lives. Let’s just imagine you wake up tomorrow morning and civilization’s collapsed and then disappeared. And you have to ask yourself, “What do I actually know how to make or do? How could I go about rebooting civilization in the way you’d reboot a computer after it’s crashed?”

Lewis Dartnell: So basically page one, chapter one of the book, I look into slightly different scenarios about what situation you might find yourself in, and how that would modify or change the trajectory you need to go through to try to recover. And as you’re asking about, for many good reasons we would have to reboot civilization — after some kind of global catastrophe, some kind of doomsday event or apocalypse — along a different trajectory, along different developmental lines than we did the first time around in our own history.

Lewis Dartnell: Things like access to fossil fuels, to cheap energy. Coal and oil is going to be very different today than it was in the 1700s and 1800s, because we basically sucked up and dug up all of the easily accessible oil. Although there’s a lot of coal left quite close to the ground in places like China and Russia. So I play around with ideas of a reboot or a steampunk history — how you’d have different mishmashes of technologies being reinvented in a different order to what happened in history 1.0, if you like.

Rob Wiblin: So it sounds like you think probably energy is the big issue, or the most serious bottleneck that people might face when they’re rebuilding?

Lewis Dartnell: Well, I sort of break down the components — the Lego bricks, if you like — of our modern world, of the current technological civilization. And in each of the chapters go right back to the basics of, “Why do we need this? What does it do for us? How is that hiding behind the scenes in ways that are probably invisible to you if it’s being done right in the modern world?” And it is energy: energy is, of course, important. But also materials. You learn about at school in the different ages of human history — of the Bronze Age, of the Iron Age, of the Steel Age — and titanium, aluminum, and tungsten, and all these exotic supermetals that we now use.

Lewis Dartnell: And within the aspect of metals: even if you were trying to reboot, to recover — let’s say 1,000 years after whatever the event was that collapsed everything — the metal might have been dug up. It’s not going to be underground anymore, but it’s still there. It hasn’t been consumed. It hasn’t been destroyed. And even very, very corroded metal is basically now just a very rich oil you would’ve dug up anyway. So you’d apply exactly the same technology to smelting and then blacksmithing and forging the bones of a collapsed skyscraper 1,000 years in the ruins of Manhattan or London, that we did in the 1600s and 1700s.

Lewis Dartnell: So what I try to get at in The Knowledge was using this thought experiment — this playful hypothesis, this scenario of the post-apocalyptic world — to answer as a genuine question. But by doing so, looking into our own history and how we got to where we are today, and why the world that we live in looks the way it does.

Rob Wiblin: I guess one challenge that fits in between material and energy is concrete, which is a material that would be very abundant after the apocalypse, but somewhat difficult to repurpose. More difficult to repurpose than metals. And it’s a material that requires an enormous amount of energy to produce.

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. So I’m a bit of a concrete fan, and I got massively into concrete when I was researching The Knowledge. Because when you think about it, it is an absolute wonder material. It is much maligned nowadays in 1960s regeneration and godawful-looking buildings. But when you think about it, it is liquid rock that humans have invented: you mix some stuff together you’ve dug up from underground, and then pour this slurry into a mold, and then it sets — hard as stone, hard as rock — in whatever shape you want it to be. Things like concrete and cement go right back to the ancient Romans. And when you mix concrete technology with steel and reinforced bars, you now have something which is incredibly strong in both compression and tension. It absolutely is a wonder material.

Lewis Dartnell: But as you say, even though there’s going to be lots of this concrete lying around after the apocalypse, it’s hard to get at and to reuse, because it is now just lumps of rock. And one of the problems of the modern world, and in climate change and in global warming, is the immense amounts of CO2 which were released in creating concrete. But I think you would probably want to reuse concrete as a very good option whilst going through a recovery after whatever might end our current civilization.

Luisa Rodriguez: Cool. Interesting. I was thinking about coming back to the physical and energy issues in a later section, but as far as The Knowledge goes, the book wonders about how we could rediscover essential information — like germ theory, for example. I wonder if we can fix any of that ahead of time, if it isn’t already — I don’t think it is for most things — by storing some of that information somewhere safe, maybe multiple places across the world, so that it could be rediscovered if it was ever forgotten.

Lewis Dartnell: One of the ideas I played with in The Knowledge was what would you most want to whisper in someone’s ear — like 2,000 years ago, or if someone’s having to go through this process again — that once you’ve told someone, it kind of makes immediate sense. Or you give them a very simple set of instructions for how they can make something or build something or demonstrate something for themselves.

Lewis Dartnell: And for me, the one that stood out by far the most significantly was this idea of germ theory and how that links to the microscope. Imagine the centuries and centuries and centuries of human suffering through history, because we didn’t have the right idea about why people got sick, and why they died, and why plagues seem to spread very quickly through cities and from person to person.

Lewis Dartnell: So if you told people that the reason people get sick isn’t because of bad air — mal aria, from the Italian — and it’s not because some fractious God has smited you. It’s because there are things which are invisibly small, they’re so tiny you can’t see them with your naked eye, but they’re there and they get into your body and they multiply and you pass them onto one another. But tell you what, this is how you make glass from scratch. And I give the recipe in the book.

Lewis Dartnell: And actually, one of my favorite maker projects when I was researching for The Knowledge was making some Robinson Crusoe glass from scratch. I went to a beach and I got sand and seashells, chalk, and soda ash — sodium carbonate — and made some glass from scratch in the course of a weekend. Which you could then fashion into a lens to manipulate and control light, and then build a microscope from it. And there’s nothing stopping the ancient Romans over 2,000 years ago building a microscope, if only they’d known what to do.

Lewis Dartnell: And this gets right to the core of your question there, Luisa. If you just tell someone the most useful thing to do or to try, you don’t have to stumble across that invention again serendipitously like we did in our own history — you can leapfrog straight to it, cut out hundreds of years of fumbling around in the dark. And perhaps the best way of doing that would be to build these repositories of human knowledge.

Lewis Dartnell: This idea has been couched by different authors in the past in terms of something like a manual for civilization, which The Long Now Foundation in San Francisco talks about. Or a total book: a book that contains the sum total of human knowledge, but is also organized in a way that is useful and progressive, holding your hand and leading you through the steps of the ladder. Unlike something like Wikipedia, which is an absolute mess of information just dumped in there. You might then have these repositories of the sum total of human knowledge dotted around the globe. Maybe you have some big conspicuous markers that point post-apocalyptic survivors to where their local library for rebooting is.

Lewis Dartnell: I appreciate that this is starting to sound a lot like sci-fi. And this sort of idea has been explored really well in some cracking books. But I think that’s an intriguing idea. It is something that if you took the risk of catastrophic civilization collapse seriously — and I think there’s good reasons to take that seriously — there are pragmatic, hands-on things we could be doing about that right now to dramatically increase the chance of a rapid bounceback, of a rapid reboot.

Rob Wiblin: Did you, in the process of writing the book, form a view at all on how much we’re already covered to some extent by the fact that there are just libraries all over the place? At least after a pandemic that didn’t destroy all of the infrastructure, there’d just be so many artifacts that indicate knowledge, or strongly imply knowledge, or could be reverse engineered, and so on.

Lewis Dartnell: I mean, that’s it. You could find lots of automobiles lying around, and have a good idea of, “Well, this is what this bit does. This is the piston, this is the crank, this is the cam.” You might not need to reinvent everything from scratch. You wouldn’t need to reinvent the wheel of the car; you could just copy what you find there. But I didn’t find that a particularly satisfying answer to give for The Knowledge. I wanted to show how you could actually make things from scratch yourself. Although I play around with that idea of scavenging and foraging and copying what you find around you from the detritus and the remains of our civilization, in chapter one of the book.

Lewis Dartnell: But I wanted to quite quickly move on to: “Let’s just assume a blank slate. You’re starting from scratch. You don’t get to copy stuff or scavenge or forage. How do you go back to basics and make it yourself?” And I think the problem with the sort of information that’s stored in libraries at the moment is it’s not structured in a particularly useful way. It might explain how we do something now, but to jump from level zero on the ladder to level 100 of this advanced technological civilization we live in today is too much of a leap to do in one step. You need to have that knowledge that’s structured, that shows you how to go from one to the other, and steadily pull yourself up by your own bootstraps, and combine things with each other in different combinations.

Lewis Dartnell: And if you were to design that trajectory, that pathway, from scratch, you might also start thinking about different entry points into that trajectory — depending on how hard we were hit, and how devastated the world was by whatever the event was, or how long this dark age has lasted after the apocalypse.

Can we do a serious version of The Knowledge? [00:14:58]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, that makes sense. I suppose we didn’t just want to talk to you out of general interest; there is a slight agenda here. So The Knowledge was a popular book intended to be interesting and informative and entertaining to a broad audience. But nonetheless, as you say, it would actually be quite useful to survivors in a disaster — at least if this was the only way they could get this kind of information about how to design particular kinds of energy systems and various kinds of really important chemistry that most people know nothing about, but which underpin our world today.

Rob Wiblin: I know that there’s a bunch of billionaires out there who are open to funding a major effort to do The Knowledge on an organizational scale — not of informing the general public about chemistry and science and so on, but with the sole goal of actually aiding recovery from the worst kind of disasters that we would face. So this could involve potentially dozens of people, rather than one person working for a couple of years.

Rob Wiblin: For instance, the Future Fund, which has been covered on the show before, is aiming to give away billions to projects, including some under the heading “Infrastructure to recover after catastrophes.” And they describe how they conceive of that as:

We want to ensure that humanity is in a position to recover from worst-case catastrophes. For example, we’d like to make sure that humanity has reliable access to the tools, resources, skills and knowledge necessary to rebuild industrial civilization if there were a global nuclear war or a worst-case global pandemic. We’d be especially keen to see “civilizational recovery drills”: attempts to rebuild key industrial technology with only the tools and knowledge available to survivors.

Rob Wiblin: This all sounds extremely reminiscent of The Knowledge, and you might actually have gone more in this direction than anyone else, at least as far as I know. So I’m curious to know, with the benefit of all of that experience of writing the book and seeing the reactions to it, what do you make of this idea?

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. As you hinted at there, I wrote The Knowledge for people living today. For people walking down the high street and popping into a bookshop and wanting to pick up something to read that was interesting. But I mean this genuinely: if I knew an apocalypse was coming, and I knew I was about to survive it and I could put a single book into my bunker — along with Sebastian and Davina — I would honestly put The Knowledge in with me. Because I think it is a good encapsulation of many different areas of knowledge in a structured progressive way that you could use to recover.

Lewis Dartnell: But it’s only 300 pages long — it’s only a tiny sliver of the actual information you would need. And there are lots of selective hands I had to use to get the project to work, and I missed out entire sectors of knowledge which would of course be useful — but it’s just a bit boring to read and would be too difficult to explain succinctly in a popular science book. But I would be very, very keen — and maybe we should sit down after this interview and have a chat with 80,000 Hours about maybe putting something into some of these funds — about doing this in a more serious and a more directed way.

Lewis Dartnell: And there have been other projects looking into this sort of thing. There’s the Global Village Construction Set that Marcin Jakubowski has been doing. It’s a nice complement to The Knowledge, where it’s not the understanding and the learning you need: it’s a set of tools which are mutually supportive in allowing you to build each other. So there are projects out there. But I think it would be a really interesting project to sit down and actually start planning out, scoping out the knowledge you would need and these different entry points into the pathway, into the trajectory.

Lewis Dartnell: One thing we did try a couple of times — in fact, a bunch of times when The Knowledge came out — was to get a TV series off the back of it. And do what you said: just put a bunch of people on a desert island with some basic tools and say, “All right, go. The cameramen will be following you around. But when we come back in a year’s time, we want a city here, or you to have reached some level of technological sophistication.” And that TV program hasn’t been made, but I would give my left leg to watch it. I think that would be incredibly entertaining TV, but also a good intellectual project to go through. How far could you actually get with a selected bunch of engineers and scientists and people with good knowledge, good know-how, practical skills, working together in a team and a community to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps?

Luisa Rodriguez: So if you imagine actually trying to take that TV show forward — maybe not as a TV show, but as that intellectual project that we could learn a bunch from — what advice would you have for anyone trying to implement that?

Lewis Dartnell: It’s a good question. It’s a big question. The thing I found most challenging when I was writing the book was to stop myself from jumping the gun about saying, “Well of course this must be an easy thing to do. because I can pick it up for 99p from a supermarket. How can something that cheap represent something which is difficult or a technological achievement?” And that is a trap. The only reason many things are cheap is because we have this entire industrialized infrastructure, like the iceberg under the surface you can’t see making things for us.

Lewis Dartnell: So I think the advice for people trying to go through this process for real is to really question every single axiom of our everyday life, and the things behind the scenes that we need, to “What does this break down into? And how do we make every single component, and all the tools you need to make those components, and the raw materials?” Very quickly, when you start deconstructing the diagram like that, it’s millions and millions of parts all across the blueprints of things interacting with each other.

Rob Wiblin: I guess that raises the question of, you might have formed a view on how resilient society is to disruptions of availability of particular materials or particular chemicals, if a factory goes down somewhere that produces something that seems super essential. Do you have a take of whether society is maybe more resilient than it might seem, or more fragile than it might seem?

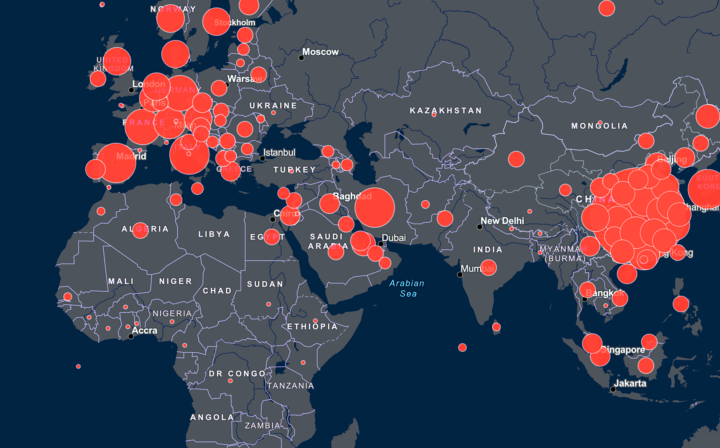

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. We certainly saw this with the coronavirus pandemic, which was never going to collapse civilization; it was never going to be that severe of an infection. But it certainly opened up a lot of people’s eyes to the fragility of our modern way of life, and the way our civilization works at the moment — with things like just-in-time delivery and raw materials being shipped across the planet to the other side of the world to be processed in one factory, to be taken all the way back again to be assembled into something which you then pick up from your supermarket. And things were starting to disappear off the shelves. People were starting to worry: “This thing I just take for granted and I rely upon — am I going to be able to buy it next week, with this minor disturbance to the global supply chain?”

Lewis Dartnell: And for that reason, it was an interesting exercise for us all to have gone through. Maybe the coronavirus pandemic will be a good clarion call or eyeopener for a lot of people, that perhaps we have been a little bit too smug in our modern world, and us being unassailable. Because there’s been modeling studies into this as well. People like Joseph Tainter have been looking into the robustness of civilizations over history. And the result seems to be that the more technologically advanced you get, the more sensitive you are to a sudden collapse — because of that interconnectivity, because of the domino effect and the cascade effects that it sets up.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I guess the pandemic made me feel better about things in a way, because so much was shut down and yet there wasn’t that much stuff that I couldn’t get. It was impressive how smoothly things went. Of course, things could break down much more if the fatality rate is 10 times higher, which is totally, totally imaginable. Then maybe it’ll be a very different story. But I suppose it made me think that society was a bit more resilient to minor disturbances or moderate disturbances than perhaps what I had envisaged.

Lewis Dartnell: I would agree with you. It was irritating when I couldn’t buy a toilet roll for a week, but it wasn’t going to fundamentally change my life. And I think you’re right: it was impressive seeing just how quickly governments and society responded to keep the essential services running, to keep the absolute critical things like food getting onto the shelves. But like you say, when you start talking about existential risks, these are orders of magnitude more than the coronavirus. There’s going to be quite a jolt to collapse global civilization.

Rob Wiblin: So you can imagine different stages for this project perhaps, or different aspects of it. One is the encyclopedia version, which is collating this information that people read in books that will hopefully be useful.

Rob Wiblin: Then I guess you’ve got the testing phase, or trying to put it into practice ahead of time phase — to see whether once you actually try to do it, you read this encyclopedia, you might be like, “This is missing all of this essential information that I actually needed. It’s a beautiful book, but not actually that useful.” So you could actually try to do it on an island as a TV show or otherwise.

Rob Wiblin: Another stage you could go to is trying to invent sort of new appropriate technologies ahead of time that might be suitable after an apocalypse. You can imagine that there might be variants on resilient technologies that we currently use in areas where it’s hard to do replacement or repair, or you don’t have access to advanced technology as easily. Basically you could try to think ahead of time about how people should do things differently after the apocalypse than what we’re doing today, and write a guide to them for that.

Rob Wiblin: Do you have a sense of which of these stages is most lacking or where there might be the most value added?

Lewis Dartnell: It is a great question again. I think the important point here is something that you mentioned: the appropriate technology, or intermediate technology. There’s no point telling this band of survivors how to make something ultra-efficient or ultra-useful and ultra-capable if it’s just too damned complicated to build in the first place. You have to start small and then level up, pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. To pick a specific example, something like a solar panel is an incredibly good way of generating electricity: you just point it towards the sky, and depending what climate on the Earth you live in, you get more or less electricity. It doesn’t really wear out, it doesn’t really need that much maintenance, and it just generates free electricity for you. And you can build yourself some kind of off-grid settlement after the apocalypse.

Lewis Dartnell: But betraying that simplicity is the fact that these photovoltaic cells we use nowadays actually use incredibly ultra-purified silicon in their wafers. It’s essentially the same technology as the microchips used in a computer. So it’d be very, very hard — particularly if you’re trying to go through a green reboot, or for whatever reason you don’t have access to fossil fuels or oil — to leapfrog all the way to solar panels, because it’s very, very hard to make the silicon that purified in the first place.

Lewis Dartnell: But there are other ways of utilizing the sun’s energy, more appropriate technologies — like solar concentrators, which use nothing more than mirrors. And it turns out the chemistry to make a mirror is pretty easy, is pretty straightforward. You can concentrate all that light onto a focal point and use it to heat water and run a steam engine or steam turbine or salt mixture to get to higher temperatures.

Lewis Dartnell: So I think what I’d be really interested to see in this kind of intellectual project is thinking about: What are the sectors of capability? What do you want to be able to do at different points of your recovery? And how do you get there in a step — which isn’t too much of a leap, but then also isn’t too short that it’s not a meaningful step, a meaningful leapfrog — that you couldn’t have just stumbled upon yourself?

Lewis Dartnell: And the other parameter to consider is, of course, all of this is dependent on exactly what caused the apocalypse, and what state the world is in today. Are there large areas of radioactive wasteland after a global nuclear exchange? Or is it more of a biological hazard that killed the people but left the stuff behind? These are going to be important factors in how you would go about recovering, and indeed how you would do some kind of recovery drill to practice to see how well it all works.

Rob Wiblin: Did you find a particular challenge when you were writing the book, other than of course making it entertaining and popular? Were there any kind of practical challenges to figuring out what people needed to know, or how it ought to be presented in a way that would be useful?

Lewis Dartnell: There’s sort of two levels of answer there. There’s how you go about writing a book that purports to, or at least the conceit is that it contains everything you’d need for the whole world — and yet fit it into only 300 pages and make it readable and entertaining. And I hint at already, there are a bunch of sleights of hand where I make things seem slightly easier than perhaps they really would be, or just missed out things, like you’ve been mentioning.

Lewis Dartnell: I think in fact, the whole of mathematics gets a single footnote in The Knowledge, where I cover my back about why I’ve not included mathematics. And of course, it’s been fundamentally useful and necessary and crucial for thousands of years. Mathematics was invented by ancient Egyptians because it solved particular problems in agriculture, for example, and then the calendar. So with those tricks in writing The Knowledge, I think there’ll be very similar tricks needed to boil down and encapsulate the knowledge you would actually need to reboot civilization in a document or library that wasn’t unwieldily large.

Rob Wiblin: Have people tried to put the book into practice? So you’ve gone out to a beach and made some glass. Have people tried to use it in other ways? And if they have, have they found that it was actually useful, or found that there were lots of missing pieces that hadn’t been noticed?

Lewis Dartnell: Yes. I did, not just the Robinson Crusoe glass, but I did a whole bunch of sort of maker projects when I was researching the book. So I could speak from authority, speak as someone who has actually tried to do this and then describe first hand how to do it, or what problems you might encounter along the way.

Lewis Dartnell: Now, for me as an author, one of the most satisfying things imaginable is hearing from people around the world. No idea who they are, they just ping me an email out of the blue saying, “Hi Lewis, found the book interesting. Good job. Thanks for writing it.” But every now and then, I’ll get an email from someone who runs a university course saying, “It’s been one of our course texts for a couple of years. The students love it. It really fires up their imagination about how to go back to basics and think things through from ground one.” And every year, I take out a bunch of the keenest undergraduates and we live in a forest for a weekend and try to put some of the things into practice. I think those sort of wilderness skills, which I dabble with a little bit in the beginning of the book, are one thing.

Lewis Dartnell: But to actually go through the process of recovering a society, the timeframe you’re now talking about isn’t a few days or a few weeks. It’s years, if not decades, if not generations. I think that’s where you’re going to have the time problem of testing this or doing drills. You don’t have a society if you have only 10 people, 100 people. A society is thousands of people, tens of thousands of people. So how would you do a drill with enough people to make it realistic, but also get the right spread of practical skills represented in that community?

Recovering without much coal or oil [00:29:56]

Luisa Rodriguez: Do you think it’s possible to design a sort of photovoltaic cell that’s simple enough that people would be able to manufacture it with much less technological sophistication than we have today? Or is that just not a thing the relevant physics allows?

Lewis Dartnell: So photovoltaic cells are a really interesting case, because they seem to be really simple technology. It’s a wafer of silicon you point towards the Sun that absorbs the energy and gives you electricity at the other end. But actually the technology behind it is pretty advanced, and to get a wafer of silicon which is pure enough to get that photovoltaic effect to be able to generate meaningful current is basically the same technology as microchips and computer chips.

Lewis Dartnell: So it has been positive. People have talked about the possibility of leapfrogging right over an industrial revolution based on coal and steam engines, and going straight to green technologies, to solar panels. But I just can’t convince myself that’s possible. To get a society which is already technologically advanced enough to be able to create the solar panel kind of presupposes it’s got the energy in the first place. I think you get a bit of chicken or the egg problem there.

Lewis Dartnell: But you can use the Sun’s energy in other ways, other than photovoltaics. You can use something as simple as a mirror — and the chemistry behind making mirrors is very easy — focus them all onto a point, boil water, run a steam turbine, heat mixtures of salts to very high temperatures. But there’s still one thing which you absolutely need in society, which is hard to do even with big solar concentrators, and that’s getting a lot of thermal energy all in the same place for things like smelting metals or creating concrete. And that’s the problem that we’ve still yet to solve satisfactorily in the modern world for using more solar energy — not for generating electricity, but creating the materials and substances that we need in our society.

Rob Wiblin: OK, so you could imagine that we’re producing PV cells the way we are today because we can. But actually there’s a worse version of PV cells that you could produce with less pure silicon. It’s like a more basic, bargain-basement version of a cell that still produces electricity from the Sun. But I guess you’re saying that actually the version that is practical is the mirrors to boil water, to turn a turbine, to make electricity. That’s the basic version that they would realistically reach for if they had to use solar.

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah, I suspect there’s probably something of a steep step function of the electricity generated by impure wafers of silicon. I mean, you’re basically talking about sort of sand, and you don’t get much electricity out of a bucket of sand. So I think it is not going to scale linearly — you’re going to have to get it pretty pure before it is useful, meaningful in any sense. But yeah, there are simpler ways of using the Sun’s energy without using photovoltaics to give you a direct current.

Rob Wiblin: Along those same lines, in the book you basically say that you think the first energy source that people should be reaching for, other than fossil fuels, is using hydropower and wind energy. Basically using these natural forces to turn a turbine, which you can then use either for mechanical work, like people have done throughout history for thousands of years, or to produce electricity. Because if you can spin a turbine, then you’ve got an electricity source with the right magnet setup. Do you think it would be possible to pre-prepare some kind of schematics for simpler wind generators or hydro generators that could be built and maintained with more medieval levels of technology, but which would be actually pretty good at generating energy?

Lewis Dartnell: Well, hydropower and wind power are ancient technologies. We exploited them first for grinding flour and timber mills. And the idea I played with in terms of this sort of steampunk reboot process in The Knowledge was if you combine that medieval technology (i.e. easily re-achievable technology) with modern knowledge — which is actually quite simple, if only you know the secret to it, of the electromagnetism and magnets and copper wires — you could create a windmill that looks medieval, but is spinning a generator to create electricity for you. You’d have this sort of steampunk, electro-windmill type mashup.

Lewis Dartnell: And so what you would want if you were to do this genuinely, is you could relatively easily prepare schematics, construction diagrams, blueprints of how to create a turbine — which is not quite as efficient as the 100-meter-tall ones you see dotted across the countryside, but is still a lot more superior to sort of Dutch 16th century design — and give all the wiring diagrams for the generator, and tell people how to make an electromagnet and make the thing work.

Lewis Dartnell: And indeed, a lot of that information resource already exists, and I was mining it when I was writing The Knowledge, because there’s a huge library, huge repository of information that’s been built up by the appropriate technology community, by the intermediate technology community. I downloaded something like 10 gigabytes’ worth — a lot of them were microfilms that had been scanned, others were PDFs. I think Appropedia is a website you can access it all through today. And 80% of it I found useless. 10% of it was interesting. And then 5% was absolute gold dust. And it was a process when I was writing the book of reading it all and sifting through the actual useful stuff.

Lewis Dartnell: So I think, were you to go through this process of creating a genuine handbook for rebooting civilization from scratch, you wouldn’t have to go right back to the beginning to create that. There is a lot of information that you could draw upon, and repurpose and reframe it in the most useful way for the question at hand, rather than sort of a 1970s textbook intended to be used in sub-Saharan Africa. You could adapt what already exists.

Luisa Rodriguez: A minute ago, you were saying that there’s a reason to think that some of the solar and other renewable energy sources might not be enough to do some of the critical energy-intensive things we’d want to be doing. And in a 2015 article you wrote — “Out of the Ashes,” which we’ll link to — you talk about some specific challenges humanity would face, having used up a lot of the readily available coal and oil.

Luisa Rodriguez: So my colleague, Will MacAskill, has written a forthcoming book called What We Owe the Future, which you and I actually both contributed to a little bit. And it argues, among other things, that this is an important reason to get off fossil fuels ASAP, so that there’s some left over for our descendants in a post-disaster scenario. Does that sound right to you?

Lewis Dartnell: So again, it comes down to which axioms you want to play around with: What was the exact scenario that necessitated everyone starting again from scratch? What state do you find the world in? And you can play around with some of those parameters, like: Is there still going to be crude oil underground — yes or no? Even if there’s not easily accessible crude oil, there’s still lakes of the stuff held in petrochemical refining stations around the world. So would you be able to get access to those? Or have they all leaked away, or have they burned, or how long has it been since the collapse before you are trying to recover?

Lewis Dartnell: I think oil is a simpler answer, because I suspect we would struggle to get access to lots of oil starting again. Geologically, there’s not a great deal of oil left, because we’ve got very good at extracting it up until now. Whereas coal is a very different matter: there are megatons of coal. There is plenty of coal left underground, and you would only need to open-cast mine it. It’s relatively easy to get to.

Lewis Dartnell: But for that Aeon article, I was playing with the idea of, let’s imagine that doesn’t exist. Let’s imagine that the collapse happens 100 years, 200 years in the future. Or for whatever reason, you are trying to recover society in a part of the world where you are not within walking distance of an open-cast coal mine. What alternatives might you go through and might you be able to use?

Lewis Dartnell: And I talked about charcoal and how you could use that to smelt metals. And indeed, it’s not just a thought experiment, because a large fraction of the steel that’s being smelted in Brazil I think is done using charcoal. They have a lot of natural wood resources, and they use them sustainably, and they make metal from their forests. So you could go through that process if you needed to. And of course, charcoal is what we used before coal in the first place. You would just be stepping back to a slightly simpler technology and not having to really reinvent anything again.

Rob Wiblin: I suppose I came away from the book and that article also having the same intuition that energy was going to be the big challenge for people after the apocalypse. But I felt cautiously optimistic that they’d be able to cobble together a bunch of different solutions that you were suggesting and kind of make things work. I mean, in order to get really high temperatures to do industrial processes, you’re saying we could use charcoal kind of like we used to. Currently that’s not practical to do on a large scale, because we need that land for food because there’s eight billion people with mouths to feed.

Rob Wiblin: One benefit that would have after the apocalypse is there’s a lot less need for food, and so there’ll be more land available to grow trees, to make charcoal, to run this kind of stuff. And also, I suppose I just have this economics-y intuition, as someone who studied economics, that the prices will move, charcoal becomes more expensive. We’ll economize on our use of these industrial processes that require really high temperatures. And it’ll be horrible, but people will find a way to kind of make things livable.

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. I mean, that’s it. By its very nature, apocalypse kind of presupposes a mass depopulation event. So there’ll be a lot of free land available that is currently growing grain to feed mouths. And you won’t even need to plant forests to chop them down for charcoal — it will re-wild in a decade or two anyway, the forests will grow back over the farms. So you would have access to lots of wood, I think, at least in the early days as you recover. And then your own population of your rebooting society will start growing again, and you’ll start hitting exactly the same base of land use threshold that we started encountering in Britain as early as the Elizabethan Age. We had chopped down all the forests near the cities and towns, and so the price of fuel, the price of wood, was starting to go up — which was starting that process towards looking for alternatives, i.e. coal.

Most valuable pro-resilience adjustments we can make today [00:40:23]

Luisa Rodriguez: I was interested in talking a bit about practical adjustments we could make now to make society more resilient in the future. We can imagine a scenario where humanity faces some severe shock, but it’s on the borderline between a situation where we experience a series of cascading failures versus get our act together while we still have access to pre-disaster technology and rebuild in a kind of orderly fashion. In that kind of case, what are some ways that we can organize things now that might make a difference between those two futures?

Lewis Dartnell: I think the idea here is, can you engineer the situation so that you fail gracefully? If you have just experienced a catastrophic shock — rather than the whole system snapping and fracturing completely — can you cushion the fall slightly, or catch your fall, so you don’t regress too far before putting yourself back up? Without wanting to bat away the question, because I do think it’s a good one, I wouldn’t know how to go about answering it. Because again, I think it’s so dependent on what was the event in the first place? What is the scenario we find ourselves in? How many people have died? What nation-states are now at war with each other over the resources that they are looking for for their own populations?

Lewis Dartnell: We’ve already talked about saving not just libraries of useful information that tell people how to go back to slightly simpler states and slightly lower technological levels and pull them back up, but repositories of the most useful tools as well — things that, again, link back to appropriate technology: things that you could repair perhaps at the village level, rather than having to send back to a factory in China to get repaired. Start breaking some of those ties of the global transport of things around the world and make it a bit more local.

Lewis Dartnell: To link this to current affairs, the EU as a whole — and the world in general as well — are starting to address where do we get our oil from? Do we continue getting it from Russia? Because this is now very problematic. Do we try to sever our connection with Russian oil and try to find it elsewhere, or — and you can probably guess what my point of view is — do we take this opportunity to fundamentally change the question and look at how we can not use oil at all? Can we go much more towards renewables, to hydropower, to wind, to solar? Can we break our reliance on something that we get from another nation-state, which they then basically use as political leverage? A lot of these topics and current affairs do link very, very directly to people looking at catastrophe studies and rebooting. They’re different aspects of the same coin.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. Nice. Are there other examples of things you might change about the way we organize society today, that you think might make us more likely to build back during that grace period rather than fall apart? Things like less electrification, sometimes we use sterile seeds, electrical grid robustness, anything else?

Lewis Dartnell: I’m not sure the answer is to try to fundamentally change society, i.e. expect every member of the population to change their lifestyle, because I wonder if that might be impossible. We’ve not been able to do that in any really meaningful way to address the problem of climate change, which is already happening and people already appreciate the dangers of. To try to get people to come on board a certainly more abstract hazard — which is, “We don’t want the whole of civilization to collapse completely, so we’re going to fundamentally change how we live our lives” — I just see that being a hard sell.

Lewis Dartnell: I wonder if a better approach would be to not try to change every member of the public, but to put into place centers, or seeds, or kernels that could be used and sort of activated if the need arises. We’ve talked about libraries of information, we talked about repositories of tools and sort of disaster preparedness: you would have a bunch of generators in a warehouse somewhere, so we could store things that would be rolled out if the catastrophe starts happening. But I don’t think the solution is to try to change society as a whole in preparation. Would you agree with that?

Rob Wiblin: I think I’m a little bit more optimistic about how there’s probably a few bits of low-hanging fruit here. Because on the margin, I think there’s some stuff that we do today, which is slightly cheaper for us now, but looks catastrophic from a resilience point of view. One example is it seems like we’re making more and more things like tractors and cars internet connected, in such a way where these items begin to break down and stop functioning if you don’t have access to a computer to debug them. Or if they can’t get regular patches from the internet, they start complaining and then break down. People after the apocalypse might not be able to get their cars working. We could slightly do some better patent control for Tesla’s vehicles by having their software updates all the time.

Rob Wiblin: That’s one where I wonder, legally, maybe we should just say all of this essential equipment has to be able to operate even if it never connects to the internet again, because there’s a possibility that the internet will disappear and we still need to have tractors.

Lewis Dartnell: I think that’s a great point, Rob, and it links quite closely to the right to repair, that there’s been a change in the legislation in the UK. That absolutely is a great idea, because again, it breaks the bond slightly between the manufacturer and the person that sold something to you — that you should be able to take it to anyone to repair, if not have a go at repairing it yourself. There’s a whole bunch of wonderful repair cafes and organizations set up to show people how to fix things when they break, to reestablish that connection between ourselves and our technology. So you’re right, Rob, there are low-hanging fruits. There are little things we can start changing.

Rob Wiblin: How big of an issue do you think it would be that most farms are currently sowing seeds where you can’t then harvest the seeds of those crops and then sow them again, because they basically just become rapidly sterile, for reasons we won’t go into? It makes me wonder, after the apocalypse, once these fantastic factories that are producing these very high-yielding but sterile seeds disappear, will we have enough seeds to sow the next crop that we’re going to need? And will people be able to find the seeds that they need in order to resume agriculture?

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. I don’t think the solution is to stop using these hybrid crops, because the reason we use them is they are so fabulously high yielding and we need that nowadays to feed the world population that we have. So I don’t think the solution is to change how we are currently doing things. I think the solution is more to just be sensible about this and keep a repository of a simple alternative to go back to — to have like a save file on our computer in case we ever have to go back to it.

Lewis Dartnell: That would be as basic as the ancient Egyptian technology of having some granaries, some warehouses, stocked with heirloom crop seeds, not these hybrid crop seeds, that you can crack open and go back to if you need to. If you needed to have sort of regenerative farming, where you can keep back seed corn and plant it next year, rather than going back to the hybrids each time. Because you’re right. You really don’t want to start losing crops, because each of those represents technology which has taken thousands of years to develop, of selective breeding.

Feeding the Earth in disasters [00:47:45]

Rob Wiblin: Another line of pre-preparation that we could talk about is currently being done by this interesting group called the Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters. They’re this medium-sized organization now that’s trying to find ways to feed people after a nuclear war, for instance. We’ve interviewed the founder of this group twice on the show.

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah, yeah. He’s a fascinating chap.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, absolutely. He’s a crowd favorite, as a guest. One of the strategies they’re really keen on at the moment is converting cellulose in wood — which would be really abundant after a disaster — into sugars that humans can actually digest, by pummeling it down into something like you’re going to make paper and then using bacteria to digest it until it’s sugar, and then humans can drink it. Another idea is using seaweed, which grows really fast and could deal with colder weather after a nuclear winter. Do you have any thoughts on whether such a project is viable?

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. I think it might be slightly harder to create wood pulp to then have wood-digesting bacteria to create the sugars, which you then eat. I think it might have come from the ALLFED organization talking about this, that actually there are already organisms that are extremely good at breaking down wood to make food, and they are mushrooms, they’re toadstools and stuff. So if you need to very quickly scale up creating food, when for whatever reason, agriculture isn’t working as effectively — maybe the skies are still dark or it’s still quite cold after a nuclear winter — you would just use bulldozers to level a forest, bash it up a bit, and then start trying to culture toadstools and mushrooms in it. Those organisms break down what is human-inedible substance, and create great food with it.

Lewis Dartnell: Another interesting idea that I came across from Vinay Gupta — I’m not sure if you’ve come across him; he’s another fascinating/very scary person to chat with — he made the point to me, when I was interviewing him for the The Knowledge, that we already have an infrastructure that is exceedingly good at getting animals in a farm to food on the plate. Particularly, this is the fast food restaurants like McDonald’s. They are incredibly efficient, because it improves their profit margin of that particular pipeline, that particular process.

Lewis Dartnell: He calculates, I can’t remember what the number was, but we have at least several months’ worth of human sustenance that is still on the hoof. I think this would be a problem for vegetarians and vegans, but if your life depended on it, you could eat mincemeat for several months with just the livestock that is around today. And then after that, you’re in dire straits, because you’ve got no livestock at all and it’d be hard to recover again.

Lewis Dartnell: But there are these really interesting ways of looking at how can we just fill that critical stopgap while we get other things up and running. Importantly, how can we use what we already have to provide that for us, rather than having to quickly reinvent something or create something anew?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I think actually, mushrooms were the thing that Denkenberger was originally obsessed with. There’s this beautiful quote from some book where it was saying something about how humans will die out and mushrooms will inherit the Earth after an asteroid hits.

Lewis Dartnell: Is it Sheldrake, maybe?

Rob Wiblin: I can’t remember the source. We’ll look it up. But anyway, I think most people’s reaction is to go, “Huh, interesting,” but Dave’s reaction was to say, “Shouldn’t we just eat the mushrooms? Humans can eat mushrooms.” I think they might have gone to this cellulose-to-sugar conversion because maybe it has a higher efficiency, or maybe it’s easier to scale up. There’s some issues with mushrooms, I think, including people don’t like to eat only mushrooms. Although I don’t know whether we enjoy eating cellulose-to-sugar slurry either.

Lewis Dartnell: Well, exactly. And this links nicely into the astrobiology research I do as well. How do we keep humans alive on Mars? Because you’re not going to be growing fields of wheat, and you’re not going to be having cows and chickens on Mars, so can we feed humans microbially generated food? Can you grow bacteria in great big bioreactors? Can you grow algae with Martian sunlight and have human food from that? The answer overwhelmingly is that you would survive on it, but it’d be a pretty grim existence, because it just tastes minging. You would be literally eating pond scum, green mush, that’s got no flavor. It doesn’t taste like anything in food from everyday life. And in terms of mental health, eating the same thing day in and day out is a genuine problem to try to get over for colonizing Mars, as much as rebooting after a catastrophe on Earth.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I guess they might have to bring an enormous amount of artificial sweetener with them on the jet to Mars. It could end up being surprisingly important.

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. Or we genetically engineer a bacterium that creates a flavor, which you then use those flavor compounds.

Rob Wiblin: Ah, that grows its own MSG or something like that.

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah, exactly. Get the umami in there.

Rob Wiblin: Are there any other resilient or unconventional food sources that people might underrate? Denkenberger’s group has actually done contract work for NASA, to try to look at these methane-growing bacteria, which would be potentially really useful in space. Yeah, it’s an interesting one to work on. I think that there’s also bacteria that can grow just from electricity.

Rob Wiblin: Anyway, these ones are a little bit unusual. I think it probably wouldn’t be large food sources post-apocalypse, but it is very interesting to think that in future we might be able to go more directly from sunlight to food than we currently do. Photosynthesis uses less than 1% of the energy that’s actually hitting the plant — it’s an incredibly inefficient process, and we have much better ways of capturing energy into electricity now. Now, we just finally need to find the second step of converting electricity into human-edible food.

Lewis Dartnell: Into food. Absolutely. But again, I think many of these solutions have already existed and people have been eating microalgae for thousands of years. The Incans were growing ponds full of spirulina. You go into a health food shop and they’ll have these little green tablets of processed microalgae, spirulina.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, yeah. I’ve seen that.

Lewis Dartnell: People have been growing spirulina for thousands of years, and people are now looking to how we could adapt that for living on Mars. Or it could be adapted to feeding people quickly if, for whatever reason, normal crops aren’t growing,

The reality of humans trying to actually do this [00:53:54]

Luisa Rodriguez: Backing up just a second, you raise the possibility that we have food that actually might sustain us, but that the mental health costs of eating foods that have no flavor could be really big. Were there other times when you were writing The Knowledge where you were like, “OK, this is possible, but there’s some social factor that’s going to make this really hard,” or “I’m going to explain how you do this in practice, but people are going to make this actually much harder than it sounds from the physics”?

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. I made an early decision with The Knowledge that the conceit I was going with was that this was going to be a popular science book: I will explain the science and engineering to reboot a civilization. But of course, it’s more than just knowledge: there’s all the psychology and sociology. And I drafted out a chapter that included a sort of po-faced, 10-step guide to bootstrapping a democracy for yourself. Then I kind of crumpled up the piece of paper and chucked it across the room, realizing it doesn’t matter what you tell people when it comes to things like that. Because, first, it’s whoever’s got the biggest gun who gets to make those decisions. But also, on a longer scale, societies need to develop organically to be ready for things like democracy. I wonder if that’s going to be a very hard thing to leapfrog to, because it only emerged under quite strange circumstances in our own global history so far.

Lewis Dartnell: But that isn’t true of science and technology. You can tell someone how to solve a universal problem: How do I make sure I don’t starve to death? How can I make materials that are flexible and strong, which are good for making tools? How do I do some basic chemistry to create acids that I can transform things with? Those problems are universal, whether it’s 10,000 BC or 10,000 AD, and you can provide the solution for that.

Lewis Dartnell: But I did toy with leaving certain knowledge out of The Knowledge, leaving certain information out of the book, such as gunpowder. It’s a somewhat easy thing to tell someone how to make — but should I perhaps make the moral decision to keep the genie in the bottle, as it were, to not release that again?

Lewis Dartnell: Then I realized when I thought about it that any technology is neither good or evil — it’s the application you put that towards. And the technology of gunpowder, yes, you can put it into bombs, you can use it to make firearms and muskets. But also, it’s absolutely indispensable for quarrying, and mining, and opening up canals, and transforming the landscape that your society is trying to live in. If we were going through this process for real, and plotting out a pathway of how you could recover, I don’t think anything should be left off the table. Even things which can be used for dangerous means, I think you’ve got to put into this sort of handbook and allow the society itself to decide — do we adopt this technology, or do we reject it? — in exactly the same way that we have these conversations today. Are we going to just accept the engineered crops? Or are we going to reject them?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. The book is relatively light on social science, which I think was a good call, because it’s really hard.

Lewis Dartnell: It’s hard. It’s hard stuff.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, exactly. I mean, engineers think they have it hard, but being an economist, that’s the real stressful job. One area of knowledge that I think actually would be quite useful to people and is not straightforward, is macroeconomics. Like what kind of currency should you use? How should you ensure that there’s not too much or too little currency — so that you neither have hyperinflation, nor are you creating recessions unnecessarily? That’s not going to be the main issue in the first few months after an apocalypse, but in the first few years it does become relevant. It is actually possible to create recessions artificially and to damage the recovery by doing monetary policy wrong. So we should have a few pages on that.

Lewis Dartnell: As I said, one of the joys of being an author is having people contact you out the blue and say they found it interesting, or tell you something you hadn’t realized. But the number of emails I’ve got from people saying, “But you missed out this incredibly important thing” — and I said, “Of course, you are absolutely right. You can’t build a society without leadership, or without psychology, or without macroeconomics.” It’s just that you’ve only got so much you can put between the front page and the back page. Perhaps I’ll get around to writing The Knowledge: The Sequel, a second part that includes things like macroeconomics.

Luisa Rodriguez: Is there anything you definitely want to put in there?

Lewis Dartnell: Yeah. I said one of the big things I left out of The Knowledge was mathematics. For simply the reason that I thought it’d be hard to make it interesting.

Rob Wiblin: Right.

Lewis Dartnell: But maths is going to be a lot of equations and diagrams, and it is fundamentally important, and a lot of maths textbooks do a good job of explaining why Pythagoras is important for making sure that your field is square, and you can calculate the area of it when you’re reestablishing your farms after the Nile River is flooded, and things like this. Maths was developed for a reason. Maths is a tool, as much as an axe is a tool for clearing farmland for you. It’s just really hard to explain in anything other than a textbook way. Unlike things like, “Guys, concrete. You might think it’s boring, but actually, it’s the most amazing material you’ve ever come across. It’s like magic liquid stone.”

Lewis Dartnell: So I avoided certain topics, either because they’re too hard or I thought it would be too boring to write about, and then for people to read about. But to go through this process genuinely, of course you need to have a section of your library on maths, and what to use that maths for. Rather than just making it abstract, it’s got to be practical and pragmatic. And other things like macroeconomics, as you were saying.

Rob Wiblin: You mentioned earlier that there’s some appropriate technology community, which you were drawing on a whole lot. I actually don’t know that much about that, so I should go away and maybe learn about this group.

Lewis Dartnell: Right. I’ve got 10 gigs. I can send you over part of it. Keep you going for your summer reading.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I might be able to do one gig. Are there any of the tools that they’ve come up with that you’re a particular fan of, that maybe should get a little bit more play?

Lewis Dartnell: There is one interesting example I came across that’s kind of appropriate technology, but also this wonderful area of bodging and sort of hacking things together that plays along TV shows like Junkyard Wars or Scrapheap Challenge. A company devised an incubator that you can use in hospitals for premature babies. There’s a huge problem, because it’s quite high tech, and they’re difficult to maintain if you don’t have that expert specialist knowledge, so it was a prime area for appropriate technology. And this company designs a baby incubator using only common car parts that you could get from any Ford dealership or any Volkswagen dealership on the planet. It used those sort of standardized replaceable parts to create this incubator. The idea being that it’s not only simple to make with locally sourceable components, but any local car mechanic can then repair it for you, and you don’t need to send it off to get repaired or fly someone in to repair it.

Lewis Dartnell: I’d say that there’s a whole area, and you can very much fall down Alice’s rabbit hole of this, of these great examples of appropriate technology. Just people being ingenious and resourceful with how you can reappropriate things and use things in slightly different ways from what their primary intention might have been designed as.

Most exciting recent findings in astrobiology [01:01:00]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. All right. You’ve been very generous with your time, but you’re a new parent, so we can’t do one of our four- or five-hour marathon interviews. But a final one is, these days a major research focus for you is astrobiology, as you were saying at the beginning — the search for life, of birth, and understanding where and how life has arisen, or where it might arise in future. It’s a surprisingly lively area with a lot of ongoing research. I know you’ve been advising space agencies on what data they could collect that could be really useful. What’s something that we’ve learned in astrobiology over the last 10 years that you think is really significant?

Lewis Dartnell: I think astrobiology has been really taking off. I mean, it’s massively launched itself as a discipline. NASA was launching astrobiology missions back in the 1970s with the Viking landers to Mars. And it went through a bit of a dark age, it kind of receded a bit, and it is really going from strength to strength at the moment.

Lewis Dartnell: I think that’s because we’ve been making huge advances in three main areas — what I call the three Es. We’ve been discovering extrasolar planets — planets orbiting other suns in our galaxy. As our techniques get better and our telescopes become more sensitive, we’re finding more and more Earth-like planets around Sun-like stars. It’s not inconceivable that in the next couple of years, we’ll have found a true twin of our home world, another Earth-like planet.

Lewis Dartnell: Within my particular discipline of biology and extremophiles, we’ve been finding ultra-hardy organisms surviving in environments on Earth that no one previously thought could be colonized, could be inhabited. These extremophiles teach us about the sort of habitable limit, the habitable range of biology, and therefore what environments on Mars, for example, Europa, we might be able to find life.

Lewis Dartnell: Then third is explorers. Our robotic technology has gotten so good that you can effectively miniaturize an entire lab onto a set of wheels, slap some solar panels on the back of it, some cameras on the front, and have our automated roboticized laboratory drive around Mars and analyze samples for us.

Lewis Dartnell: I say we’re making enormous advances in each of those three areas, such that if there is life on Mars, I think that it is a genuine possibility we’ll have unambiguous proof within our lifetime. Hopefully within my career — hopefully it’s something I can remain involved in.

Rob Wiblin: Well that’s stuff to look forward to, at least as long as we live in a world where we don’t need The Knowledge in the future.

Lewis Dartnell: Well, exactly. Let’s hope we never need the book.

Rob Wiblin: Our guest today has been Lewis Dartnell. Thanks so much for coming on The 80,000 Hours Podcast, Lewis.

Lewis Dartnell: Thanks very much for having me. Cheers.

Rob’s outro [01:03:37]

Rob Wiblin: Just a quick reminder that here at 80,000 Hours, we recently started a free book giveaway, which you can take advantage of at 80000hours dot org slash freebook. There’s three books on offer.

The first is The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity by Oxford philosopher Toby Ord, which we discussed with him in episode 72.

It’s about the greatest threats facing humanity, and the strategies we can use today to safeguard our future.

The second is called 80,000 Hours: Find a Fulfilling Career That Does Good by Benjamin Todd — that’s a book version of our guide to planning your career.

The third is Doing Good Better: Effective Altruism and How You Can Make a Difference

by recent guest Will MacAskill, a University of Oxford philosopher and cofounder of the effective altruism movement.

We pay for shipping and can send the book to almost anywhere in the world.

If, like me, you prefer audiobooks, then we can offer you an audio copy of The Precipice.

The only thing you need to do to get one of these free books is sign up to our email newsletter.

On average we send one newsletter email a week, usually letting you know about some new research about high-impact careers going up on the website, or about a new batch of job opportunities going up on our job board.

The email newsletter is pretty great, but if you decide you don’t like it you can always unsubscribe. Indeed, if you just want a book, I give you approval to immediately unsubscribe after ordering your book — that’s totally legit.

We actually launched this giveaway a bit earlier in the year, but we had to delay announcing it to you all because the offer was so popular our poor book orderers were flat out shipping all the books people were already asking for, and probably couldn’t handle the influx from all you podcast listeners.

But they’ve increased their capacity and so are now standing by to quickly turn around your requests.

If you’d like to take advantage of that and get one of those books, then just head to 80000hours dot org slash freebook.

We’d be more than happy for you to tell your friends about the giveaway if they might be interested in one of those books.

All right, The 80,000 Hours Podcast is produced and edited by Keiran Harris.

Audio mastering and technical editing by Ben Cordell.

Full transcripts and an extensive collection of links to learn more are available on our site and put together by Katy Moore.

Thanks for joining, talk to you again soon.